Shows

Seriously, yes

Place: Windhager von Kaenel

Date: -

Artists: Gina Proenza, Alfatih, Lou Masduraud, Yann Stéphane Bisso, Caterina De Nicola, Niels Trannois, Isabella Fürnkäs

Works: Insomnia Drawings

Notes on an end of meaning

Psychologically speaking, the act of moving house inhabits a paradox – it’s an affirmation as much as it is a

negation of something, of the meaning of something.

Factually speaking, Windhager von Kaenel moved in at Baarstrasse 86 in 6300 Zug.

Symbolically speaking, Alfatih greets me with a shoe.

An ambiguous heel. A conglomerate of eggplant and sugar beet. Or food.

I enter the revolving spin. An oscillating contemplation on the representation of something. A dissipating

conversation on the interpretation of the representation of a performed thing.

I would argue that art argues that to think about a thing is to think about its symbolic value, which is to think

about meaning and the power of meaning.

The shoe-heel-food-eggplant-and-sugar-beet-closed-curcuit-installation titled “Untitled” might serve as

some sort of proof of said cascade of meaning, but also inextricably ties meaning to time. I can only speculate

how my vis-à-vis might successively read the pump as something else entirely, as something more

resemblant of fibres’ decay.

But who knows…

These speculations might not bring me closer to meaning, but to my reader’s subjectivity instead.

Who programmed this AI?

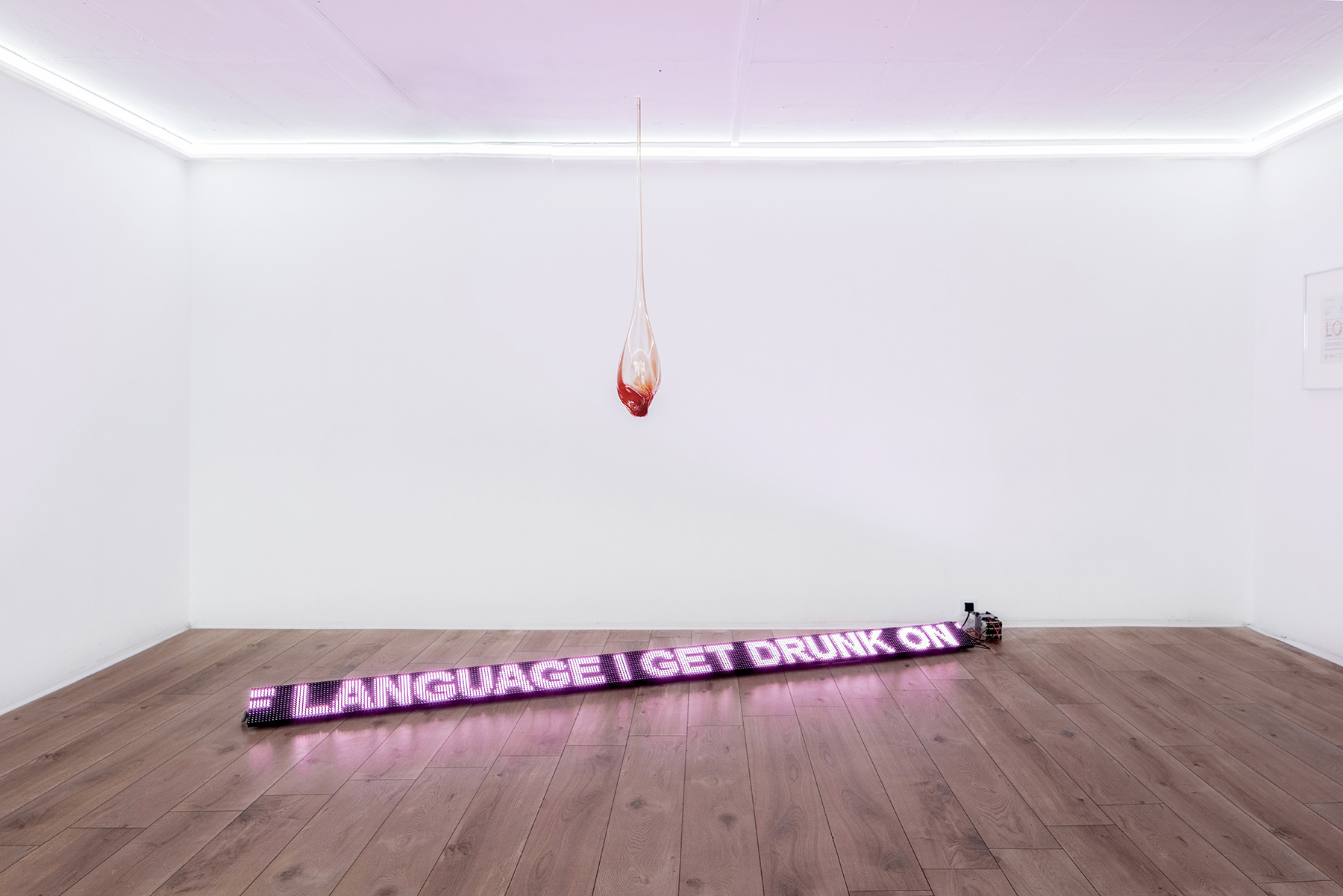

And might there be relief in Isabella Fürnkäs’ auto-poiesis and non-verbal descriptions of an inner life?

Speaking of subjectivity, what can I learn from the confusion that crawls up my spine when thinking of a collared

shirt turned into soft-haired bones?

This is a dismantled body, a fleshless body of emblematic contours.

“This is about power, about those overpowered, and this is where paradox meets”, I can’t help but think.

I think along with Lou Masduraud about the relation between my uniforms and what they entail, socio-culturally

speaking, what they might mean for me or for you.

If linguistic meaning conditions subjectivity, perhaps the way I see me will be more free, liberated from violence,

where “Long life after love” eviscerates our skeletons of their structural constraints.

All the while, light boxes advertise for dead dad DNA, a narrative lineage of sorts intertwining letters, symbols,

meaning with body and something that might be found on my chromosome, so the add suggests.

But also, DNA is Dead, so the box overts.

Dead dad DNA might hint to evidence of sorts, of past crimes, of the condemned or those who condemn.

Scientifically speaking, dead DNA is a fallacy, a chemical molecule, not really living, not really dead. Devoid

of scientific scrutiny, Gina Proenza’s choice of words might hint at the killing of something else entirely.

An intrusive thought: Kill meaning. It’s a tautology.

Philosophically speaking, I read “Dead / Dad / DNA” to be in line with a poststructuralist mode of deconstruction,

with which to deconstruct the system of meaning, in which any attempt to locate the origin of

identity or history must inevitably find itself dependent on an always-already existing set of linguistic conditions.

Thus, ontologically inherently idealistic.

I also speak of an ontological hauntology. This, too, holds a paradox, as Derridean hauntology describes an

ontological disjunction. A temporal fracture where presence (especially socially and culturally) is replaced

by a deferred non-origin.

“The opposite of the word “empty” isn’t “full”, there’s only “non-void”, a word that is defined solely by its

negation”, I think to myself when I inspect the empty shelves.

“Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. At once they return and make their apparitional

debut”, I think to myself when I further inspect the emptied shelves.

They invite me to think of ghostly creaking, doors flung open, and ghostly crackling, eyes wide shut.

I think of the concept because the reference has been made in an interview with Caterina De Nicola I have

previously read, but also because of the cupboard’s uncanny nature and the re-contextualised relics-letters

on its side:

DIS – PAIR

I cannot decide whether to feel weird or to feel eerie.

Devoid of functionality, and even meaning, possibly, the objects-letters become ornaments pointing at

something else entirely: Towards despair, as suggested by the words.

Honestly speaking, there is nothing more desperate than being stuck in despair, it’s an emotion of negation as

the complete lack of euphoric vision and futurity, ultimately, defies its presence. Haunted by past meaning, possibly,

in taxidermy the preservation of the already-dead, equally and again, negates linear temporality.

A post-modernist presence, as in Caterina De Nicola’s sense, where, even though meaning’s been killed, it returns

never coming to an end.

“Despair, therefore, ironically contains the cosmic immensity of nothingness”

“Nothingness” is as much a negation as it is a contradiction because nothingness is the contradiction of existing

nothingness.

Not sure if anyone understands what I’m trying to say, but what I’m trying to say is that one can never get to the

end of meaning: words define themselves and then they are used to describe each other.

Like I will make use of words that have already been used to describe Yann Stéphane Bisso’s and Niels Trannois’

works in previous writings. I wonder if works define themselves and then they are used to describe each other…

Yann Stéphane Bisso doesn’t greet me with a shoe but with two bare feet instead, spatially isolated, seemingly

floating but in relentless forward motion. There is a bright white flower, star or symbol of something other in the

corner, spatially isolated, seemingly floating, it might mark a hybridity of sort, of space, of time and possibly

meaning, too.

On second glance, Niels Trannois greets me with a shoe too.

A black laced heel amongst other depictions of eyes, the birth of a child, might-be-letters, many more eyes, and

a peacock peeping over a wall onto something past or unforeseen.

The painting-collages seem to elude my presence, like memories or their in-betweens. Still not entirely sure

what that means or translates to, but I no longer mind as “the untranslatable is that which cannot cease to be

translated”, I paraphrase Fabian Windhager paraphrasing Barbara Cassin.

Or like memories, that, in the end, can only be recombined into allegories of a loss of meaning.

But the past seeps into the present.

And semantically speaking, losing meaning means winning some.

Antonia Truninger, 08.06.2024

![Metamorphoses of Control [Catalogue launch]](https://media.isabellafuernkaes.com/Isabella_Fuernkaes_Mouches_Volantes_Metamorphoses_of_Control_2022_00001.jpg)

definitively_Goeben_Berlin_2020_00003.JPG)